by Zach Bethune, Thomas Cooley, Espen Henriksen, and Peter Rupert

Is Europe about to repeat Japan’s lost decade? Six years after the Great Recession began, the Euro area has shown little sign of sustained growth. Japan’s so called lost decade began in 1991 after several decades of rapid economic progress and sustained increases in asset prices that were suddenly reversed. The average growth rate of real GDP per-capita declined from about 3.5% per year in the 1980s to about 0.5% per year in the 1990s and was accompanied by rapidly decreasing equity and real-estate valuations. But, when we compare the performance of Japan’s economy with the European economy since the beginning of the Great Recession it is clear that Europe is in far worse shape than Japan ever was.

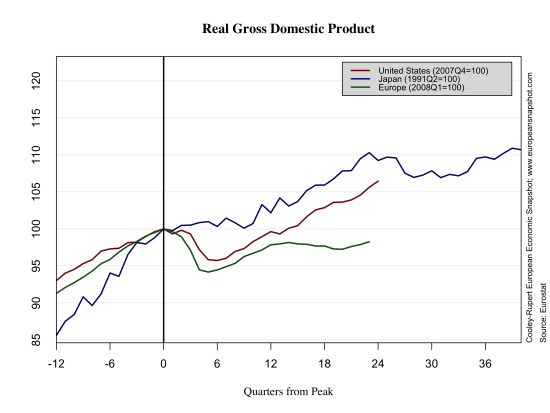

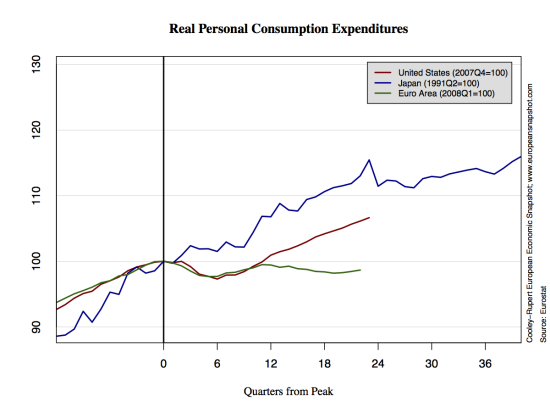

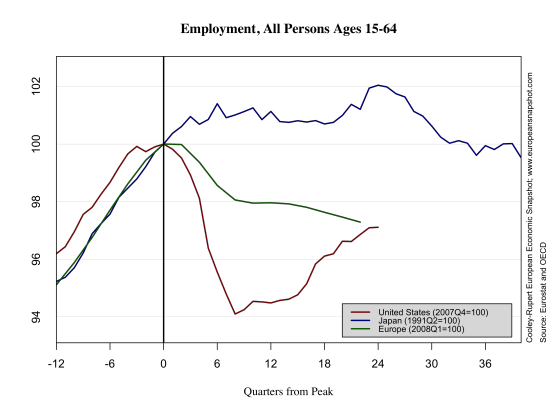

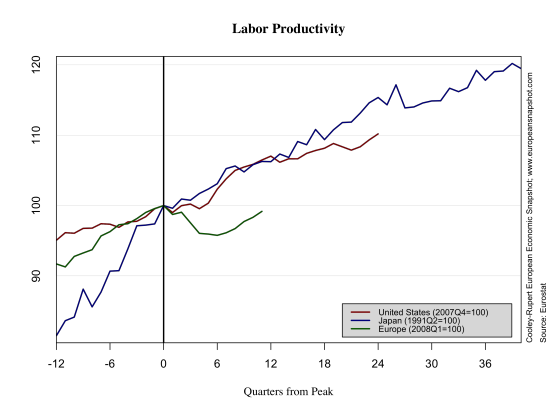

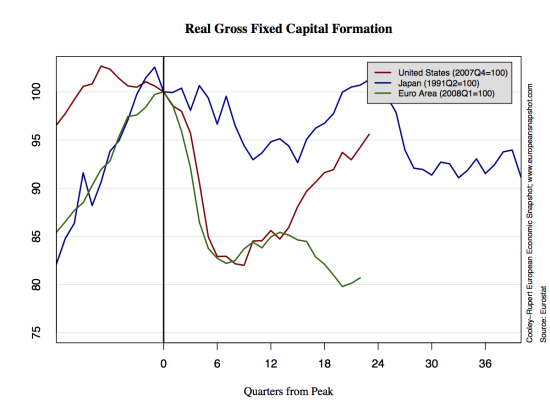

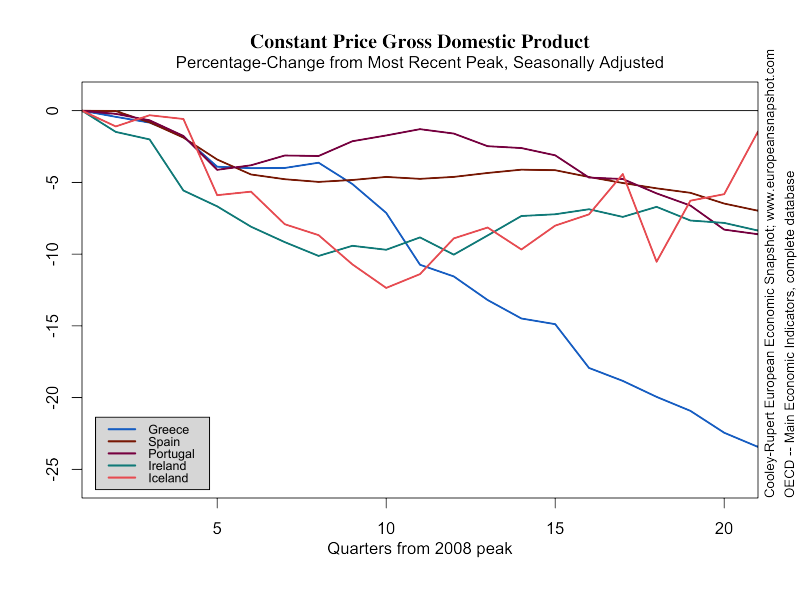

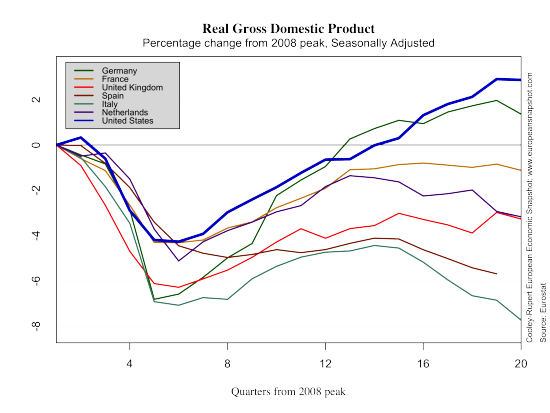

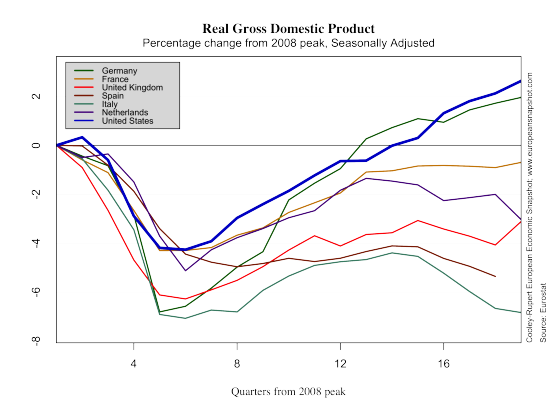

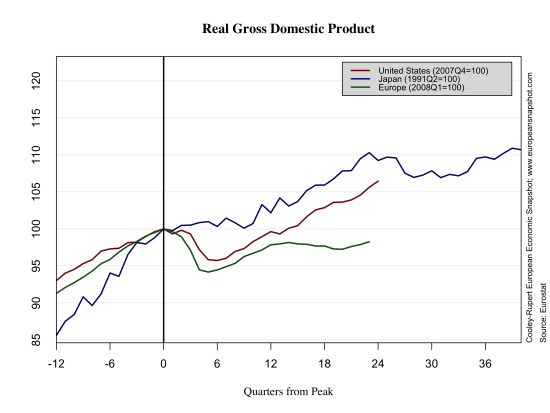

The following Snapshot-style comparative charts show the paths of key economic variables in Japan after the peak of its equity and real-estate valuations and contrasts these with the paths of these variables in the U.S. and Europe in the years since the onset of the Great Recession. For Europe and the U.S. we set time “0” at the peak before the Great Recession. Judging from this and the charts that follow, halfway into the decade following the onset of the Great Recession, the performance of the U.S. and, in particular, the European economy are substantially weaker than Japan’s economy was halfway through its lost decade.

Japan’s growth rate slowed dramatically at the beginning of their lost decade – GDP rose only 10% in the first six years and then flat-lined more or less completely. Europe, by contrast fell by six percent in the first six quarters and then flat-lined at a level three percent below their peak. The U.S. stands in contrast to both of these stories – after falling by nearly four percent in the first six quarters U.S. growth has been steady at a rate slightly less than before the collapse.

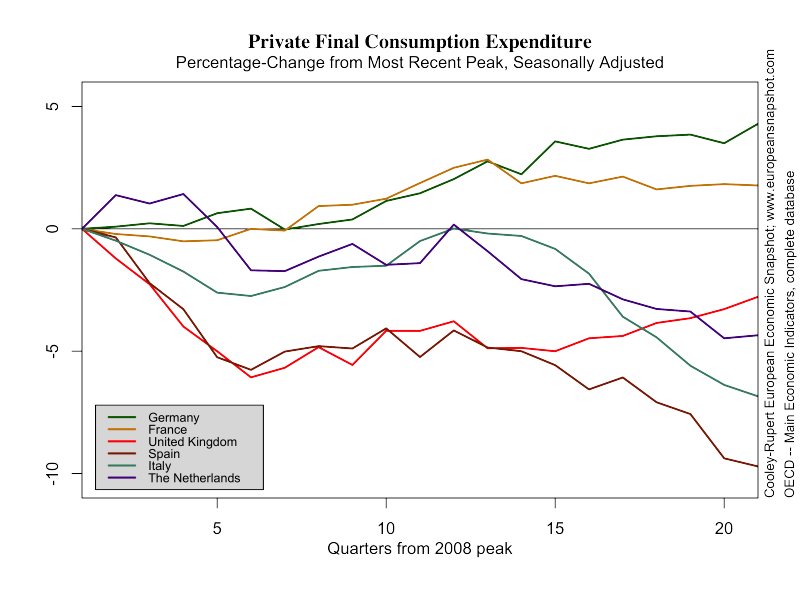

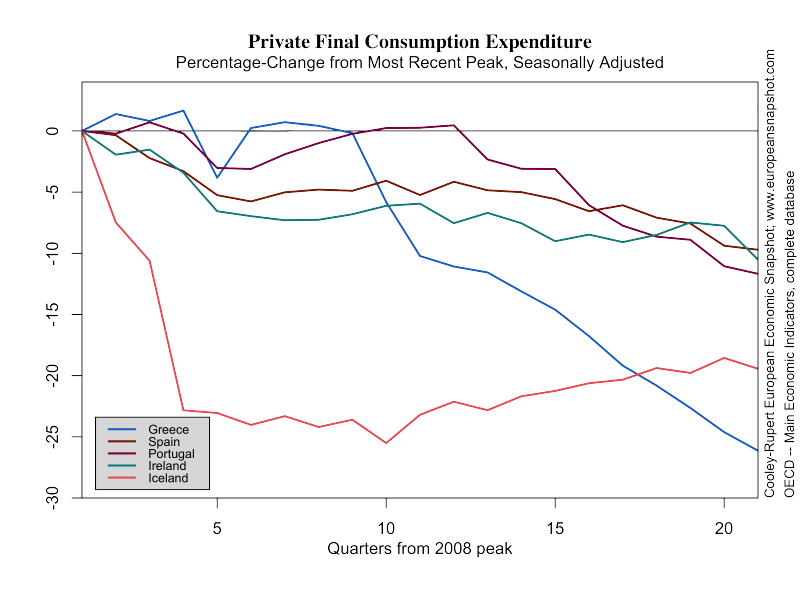

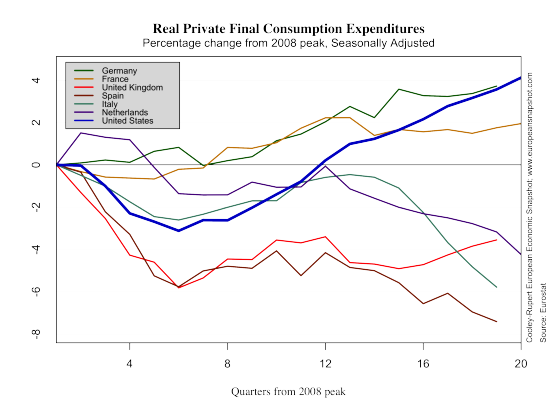

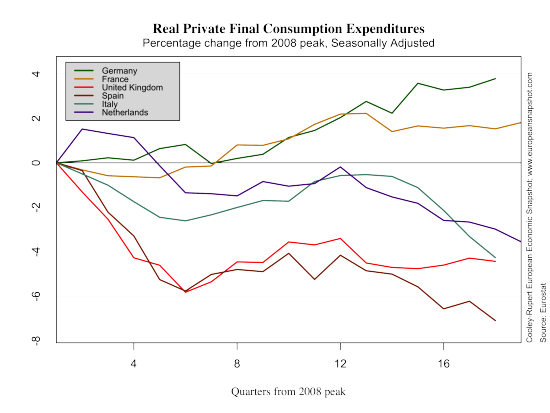

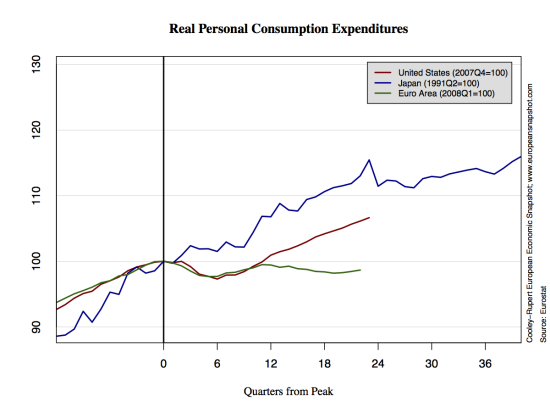

Consumption paints an even more dire picture for Europe. During the lost decade in Japan consumption expenditures never really slowed down. In the Great Recession, U.S. consumption fell initially for about 6 quarters and has been rising ever since. Europe on the other hand started out similar to the U.S. for the first 6 quarters but then consumption growth stalled and has not improved since. It has not returned to its 2008 peak.

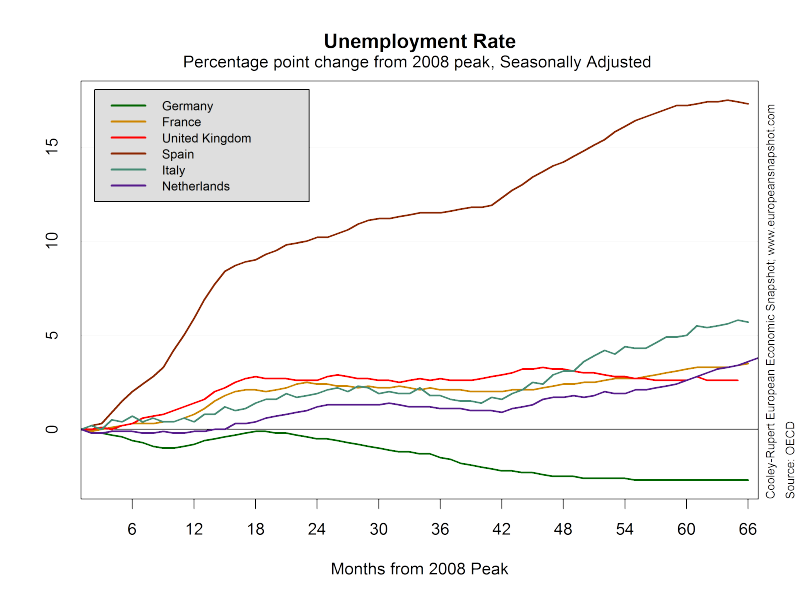

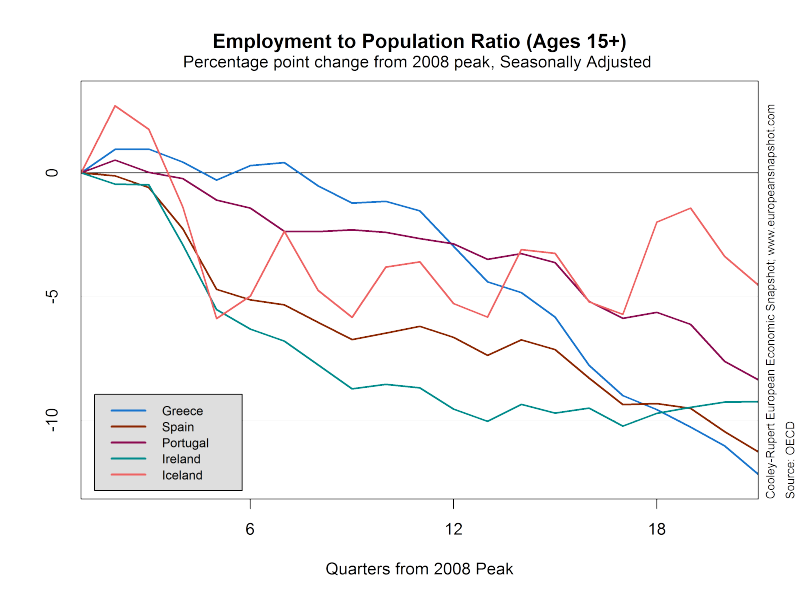

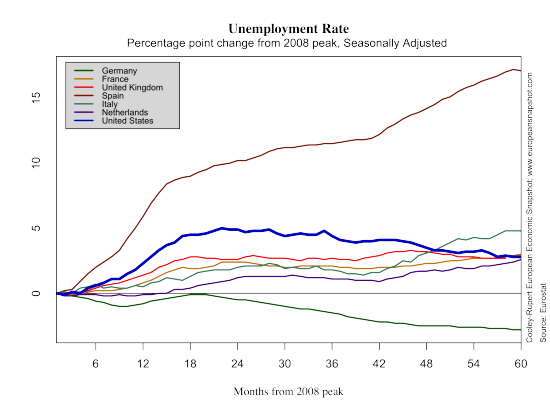

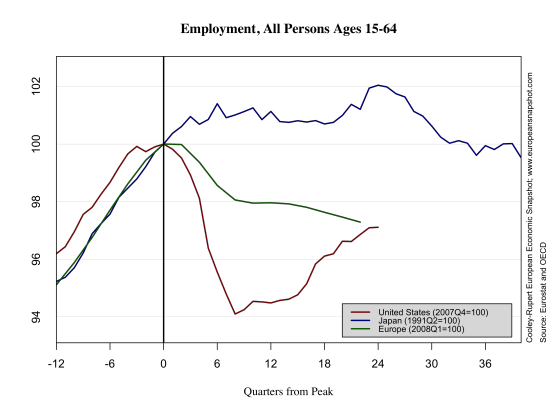

The labor market picture for Europe is even more discouraging and strongly reinforces the message of a lost decade. The unemployment rate in individual countries like Spain and Italy has been widely noted. But, here we focus on aggregate employment and the data are for the EU-28 which includes some countries, like Germany, where the labor market has not really declined. Japan, Europe and the U.S. showed remarkably similar paths of employment up until the inflection point following which there was a sharp contraction in both the U.S. and Europe. In Japan, employment like output, simply stagnated. In terms of a recovery, the U.S. labor market, after a sharp decline, is showing slow growth while Europe looks to be stuck at a permanently lower level.

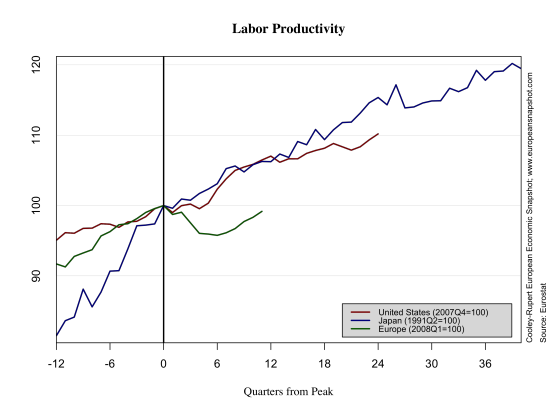

While the declines in employment were steep in both the US and Europe, the path of labor productivity has been very different. In the US the recession had a negligible effect on labor productivity, which has only recently started to show signs of slowing down (see here for instance). Europe on the other hand experienced a sharp drop in productivity at the beginning of 2008, when it fell by nearly five percentage points. Data until 2010 suggest that European productivity hasn’t shown any signs of ‘catching up’ to its previous growth trend. Measuring labor productivity is particularly difficult for Europe because one needs a measure of total hours worked. Ohanian and Raffo (2011) do the heavy lifting by constructing this series for many European countries, although it is only available until 2010.

Why the Lost Decade?

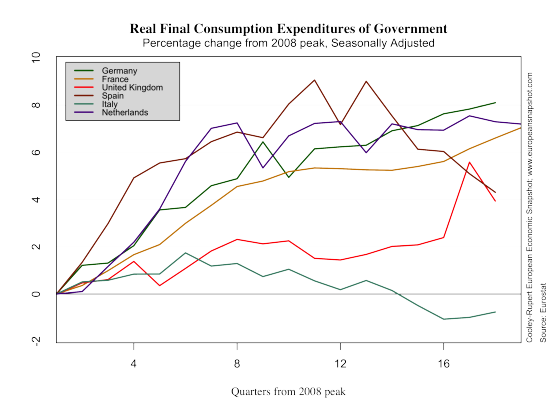

Economists have offered a range of different explanations for Japan’s lost decade: (i) the government failed to deal with undercapitalized banks that were allowed to carry “zombie” loans on their books and did not have the capacity to finance new investment, (ii) a sharp drop in productivity caused desired investment to be low, (iii) frictions caused by labor law amendments in the late 1980s resulted in declining work weeks, (iv) the monetary policy response was too timid (something Abenomics is finally trying to remedy), and (v) Japan’s prospects for recovering were seriously hampered by persistent deflation. While it is not clear that there is one compelling account, all of these elements undoubtedly played some role and all of them loom large in the current European experience.

As in Japan, European banks are most likely under-capitalized and carrying loads of overvalued (“Zombie”?) sovereign debt on their balance sheets as well as other assets of dubious quality. The European Central Bank has only gingerly approached the problem of looking at asset quality in European banks, promising to deliver results later this year. But then what? There is no plan for dealing with under-capitalized banks. In contrast to Japan and the U.S., there is no common bank regulation or resolution mechanism and there has been only tentative progress toward creating it.

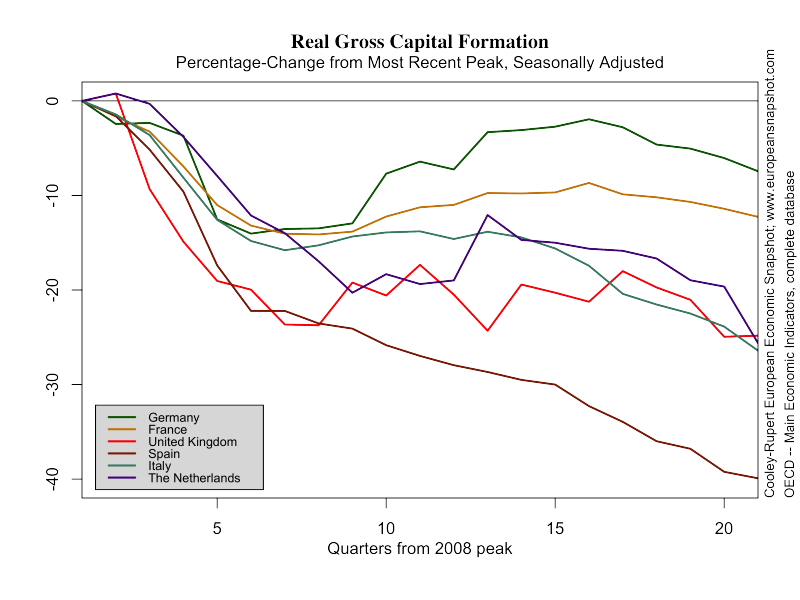

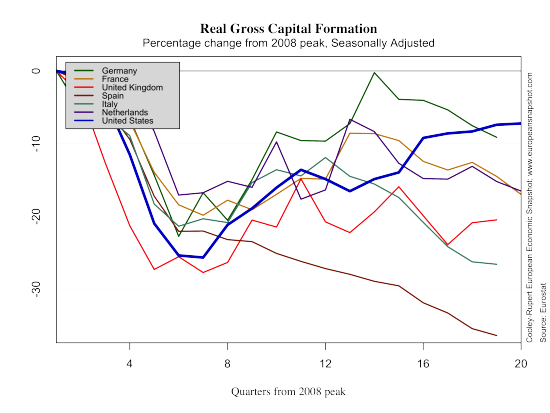

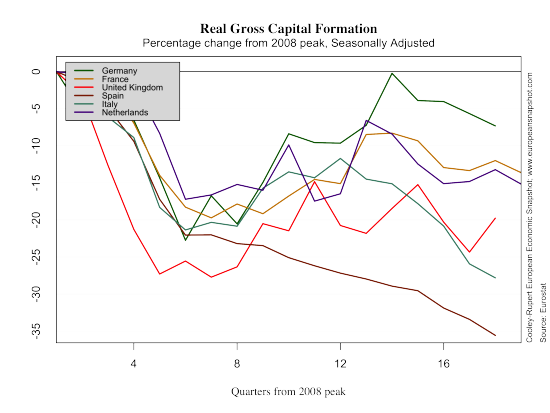

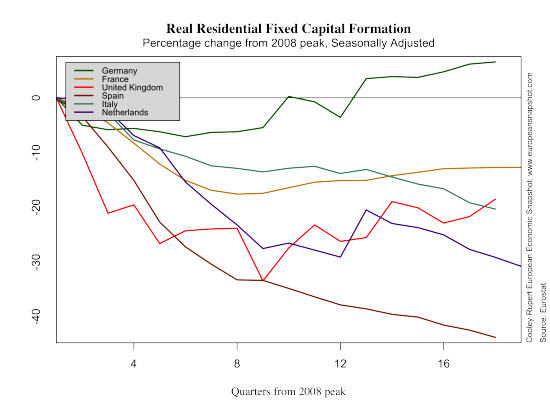

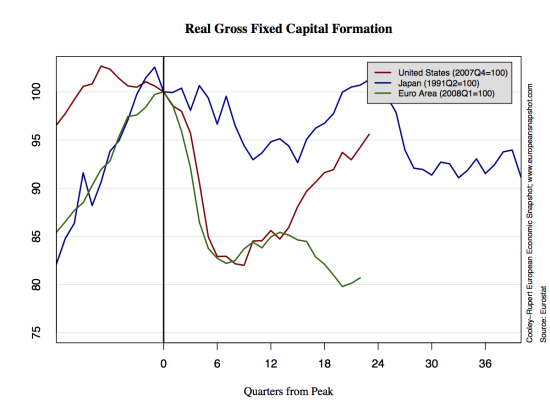

As the picture below shows, investment / capital formation stagnated in Japan, both consistent with the slower growth in total factor productivity and insolvent banks that deterred lending. The picture also shows that investment in both the United States and Europe fell relatively more at the onset of the Great Recession than investment in Japan did at the onset of the “lost decade”. In contrast to both Japan and Europe, U.S. capital formation has rebounded after an initial collapse. Again, the European situation looks more alarming than the situation in the United States and Japan.

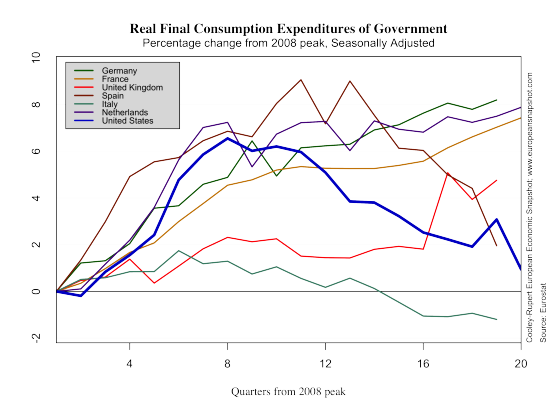

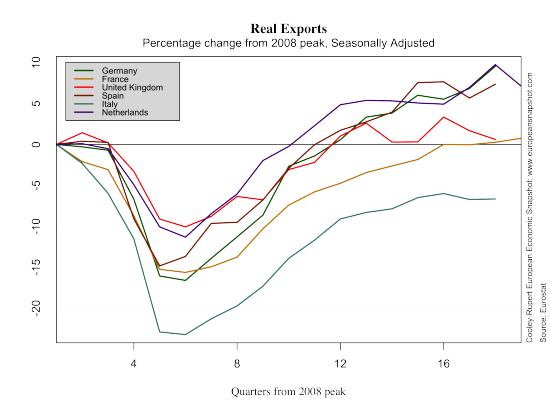

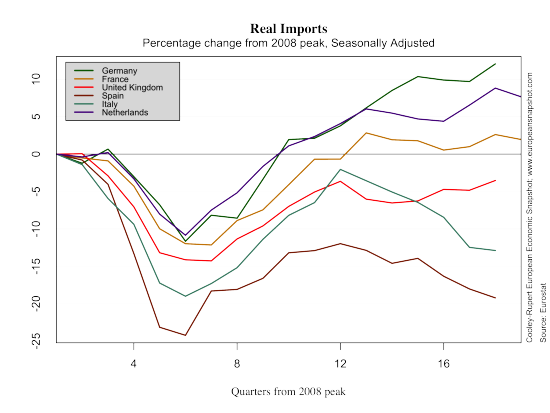

Whatever the reasons may have been for Japan’s ‘lost decade’, one thing is certain: more than halfway into the decade following the start of the global recession in 2008, the European economy is far worse and deteriorating. Even though economic growth in Japan stagnated in 1991, the economy continued to grow. In contrast, the economy in Europe has contracted and is, according to all measures of economic activity surveyed in this post, at a lower level than they were five years ago. Unless economic growth in Europe rebounds within the next couple of years, Europe is headed for a substantially worse decade than Japan’s. Surprisingly, there has been recent optimism about a European recovery, but the data do not seem to support it except for possibly Germany and the U.K.

Just as there were no quick fixes for Japan during its “lost decade”, most likely there are no quick fixes for Europe’s economy. The challenges lie in fostering economic institutions that create individual incentives and market structures that both discourage rent seeking and encourage and allow people to use their efforts to develop and produce goods and services other people value. On this score Europe has failed. They have not reformed institutions sufficiently to make their markets globally competitive and adaptable. Until they do, Europe will continue to face the possibility of an entire decade of lost income, consumption, and jobs.

Like this:

Like Loading...