by Thomas Cooley, Ben Griffy and Peter Rupert

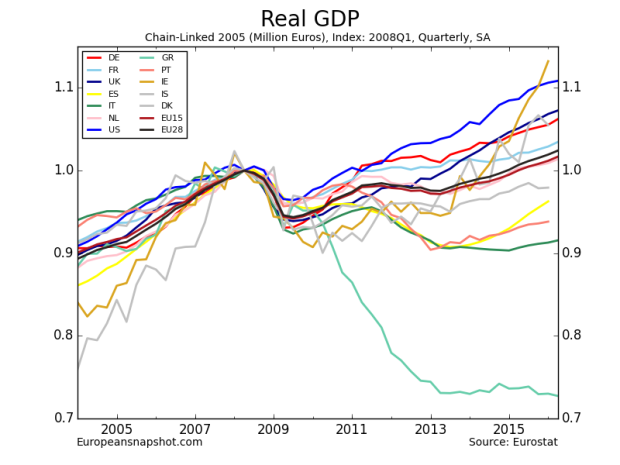

Much discussion continues about a potential “Brexit,” a British exit from the Eurozone due to the belief that the Eurozone does not help the British economy. Leaving aside the merits of the policy for the UK, we are going to describe the implications of such a policy on the specter of recovery in the EU. As we alluded to in a previous post, the recovery is less-pronounced, and perhaps non-existent if we exclude the UK from figures on GDP. Here, we include observations on additional series that confirm the same conclusion: the UK is integral to our perception of the Eurozone’s recovery, and its removal would lead to different conclusions about the EU’s economic health. As it stands, the Eurozone has shown a modest recovery, primarily driven by the UK, France, and Germany:

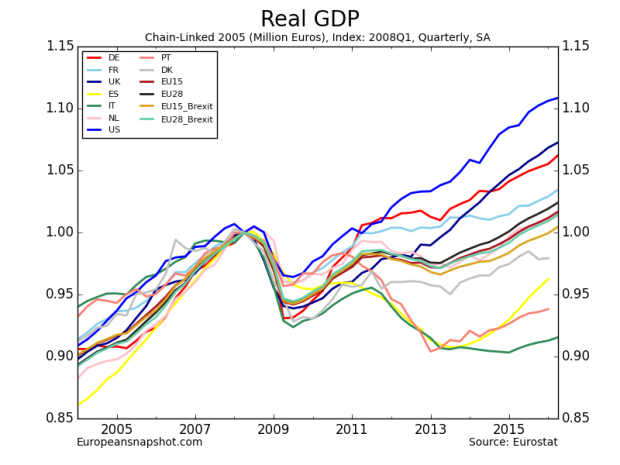

For reference, EU15 is a subset of the Eurozone including the largest economies (link); EU28 includes all 28 Eurozone economies (link). Once we remove the UK from the Eurozone, the post-recession recovery looks as follows:

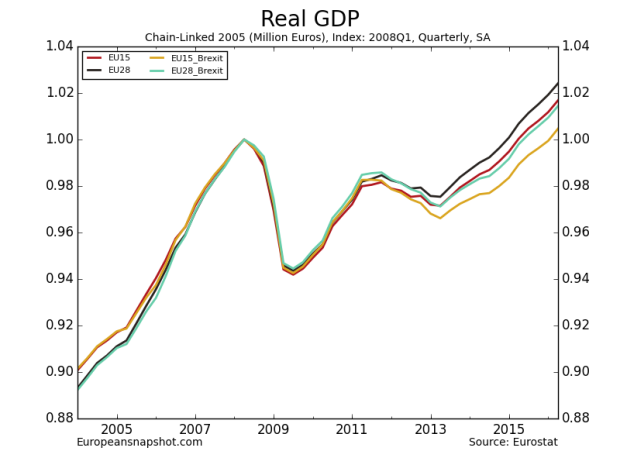

Zooming in specifically on the aggregated figures,

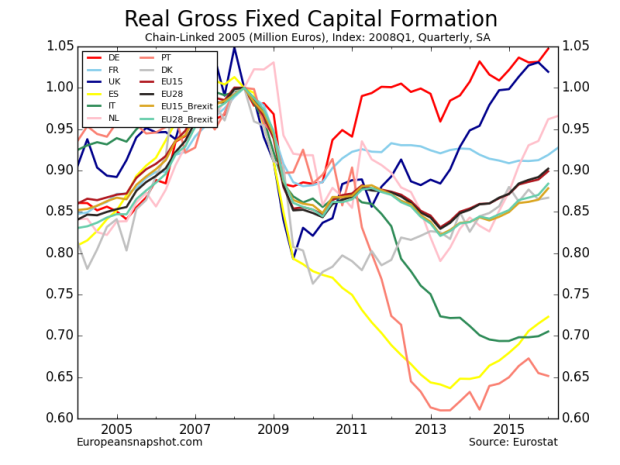

Rather than over a year of GDP levels in excess of the Eurozone’s 2008Q1 level, the Eurozone would have breached its 2008 levels just this quarter, according to its EU15 numbers. Specifically, GDP would be 2 percentage points lower, and the recovery would be about four quarters slower than current figures. Other indicators of regional economic health, like consumption and gross fixed capital formation show moderate declines as well, though not at the same scale as rGDP:

The series on fixed capital formation in particular points to an unnerving truth for the Eurozone: the UK has been one of two drivers of the recovery, the other being Germany. While other countries have been scaling back their economies, the UK and Germany have been increasing investment.

But the UK is only one domino in the Eurozone. Obviously there has been much ink spilled over Grexit. There has also been talk of Italy returning to the Lira, which we term a “Rexit.”

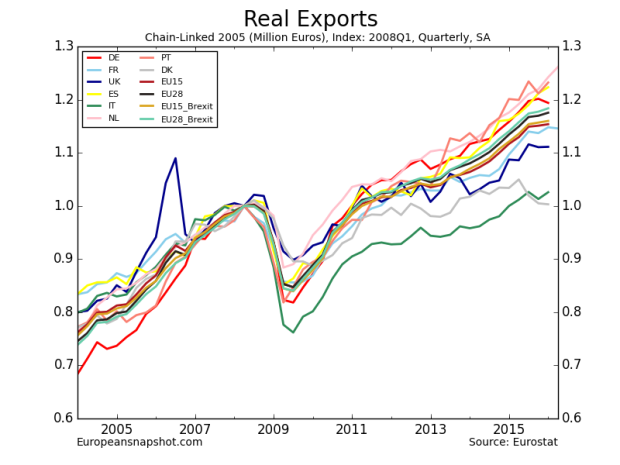

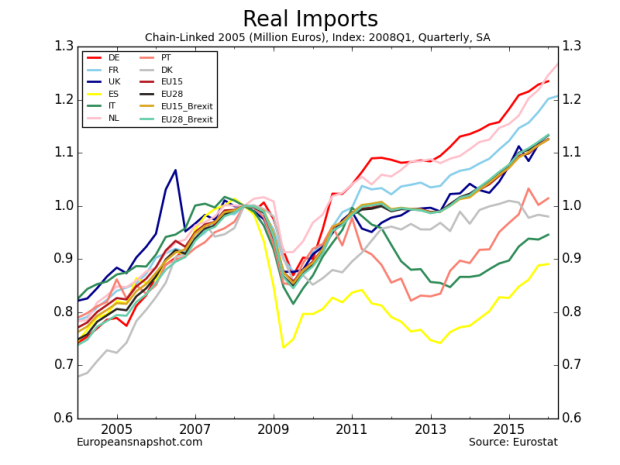

Much of the recovery in other European countries appears to be driven by increased exporting activities:

If Brexit signals that it’s time for other countries to leave the Eurozone (and equally important, drop the Euro), the consequences could be large for intra-Europe trade.There is much talk in Europe of The Netherlands being the next to go if the U.K. leaves As noted by the ECB (link), trade within member states made up 39% of GDP in 2012. With exports driving much of European growth, a decrease or even a slowdown in exports could put at risk the short-term recovery of the region. The UK vote on Brexit takes place on June 23rd, and is certainly worth following.

This article talks about the EU and the Eurozone as though they were interchangeable terms. They aren’t. Whilst being part of the EU, the UK isn’t part of the Eurozone (or Schengen and a handful of other aspects..), Indeed the Eurozone (officially the euro area) only includes the 19 of the 28 European Union (EU) member states which have adopted the euro and are in a monetary union.

I’d also argue that leaving the EU is considerably easier for the UK because it is one of the members that is most on the periphery, not being part of the Eurozone is a large part of that. The UK won’t have to re-establish a currency (As the Netherlands would if it left the Euro, the EU or both) and there is, as far as I am aware, no mechanism in place to gracefully quit the Eurozone.

All in though there are some points that are worth taking into account, not least that the Eurozone seems to do less well broadly than the non-EU economies, that applies both in terms of growth and unemployment. It also is in desperate need of further integration, something more or less accepted by the non-Eurozone states (and explicitly noted in the UK’s pre-referendum negotiations with the EU). As long as the UK is part of the EU, and as long as there is the possibility of the Eurozone countries voting as a bloc on other areas of EU governance, there will always be countries pulling in opposite directions and the integration and mechanisms that the Eurozone need will be hard to implement.

On that basis you could argue that the UK leaving will help the EU generally put its house in order, although that might mean some of the other periphery countries decide that their future is outside of the EU too.