By Thomas Cooley, Charlie Nusbaum, and Peter Rupert

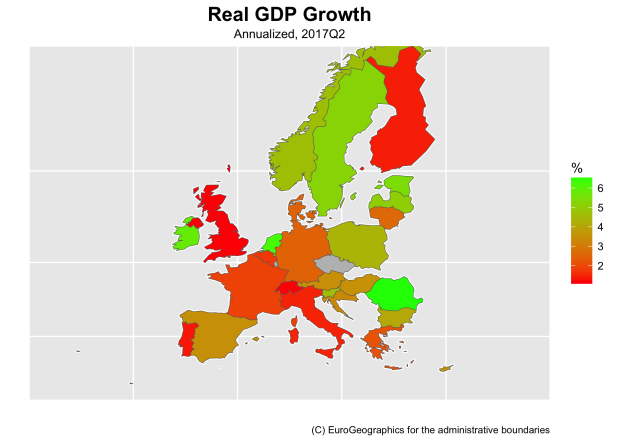

The good year for Europe continues, according to the second quarter numbers released by Eurostat this month. Indeed, annualized quarterly GDP growth for the Euro Area rose from 2.2% to 2.6% during 2017Q2, while that for the Union as a whole increased from 2.2% to 2.7%. At first glance, it may seem as though the EU lags the United States, which grew at an annual rate of 3.0% during the second quarter of 2017 (here). Compared to this time last year, however, the EU grew marginally faster (0.2 percentage points) than the US.

The Czech Republic, which we have omitted here, far outpaced the rest of the EU with an annualized growth rate just over 10%. The Netherlands and Romania also saw significant growth of 6.2% and 6.5%, respectively. Several countries, however, continued to struggle this quarter. Italy, the UK, and France saw meek growth ranging from 1.2%-2.0%. Portugal and Finland also seem to have deflated compared to their first quarter performance with annualized growth decreasing by 2.6 and 3.3 percentage points, respectively.

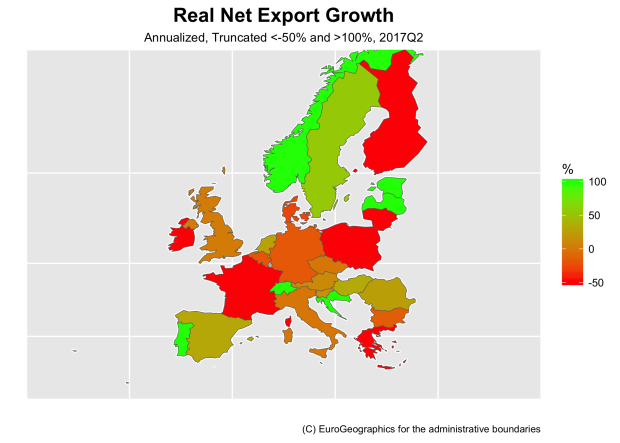

The European Union improved its trade balance as well, with net exports for the EU28 growing at a 10% annualized rate during 2017Q2. Here, we have applied a top- and bottom-code of 100% and -50%, respectively. Clearly, Portugal, Switzerland, and Norway, among others, more than doubled their net exports this quarter. Ireland, France, and Greece on the other hand, saw their net exports halved. Hungary, Spain, and Sweden also saw high net export growth, ranging from 32% to 55%; whereas Germany, Belgium, and Denmark shrank net exports by 21%-48%.

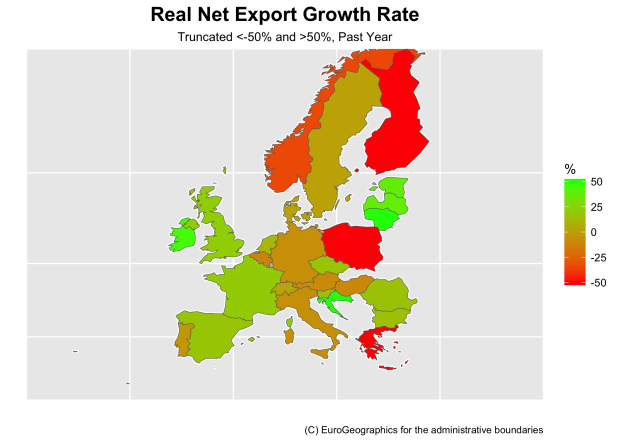

Because international trade can be quite volatile, it is often more instructive to compare the change in imports and exports over the past year, rather than constraining ourselves to a quarterly analysis. Compared to this time last year, the vast majority of EU countries are doing quite well. The Union as a whole saw net exports grow by 6.7% since 2016Q2 and the Euro Area increased the same by almost 10% this past year. The Eastern and Western economies were the primary drivers of this growth with countries such as Hungary, Malta, and Lithuania improving their trade balance by over 50%. Ireland, the UK, and France, experienced more modest yet impressive rates of 45%, 21%, and 20%, respectively. Finland, Poland, and Greece on the other hand decreased their net exports by roughly 50% each. Many of the central European countries also saw negative net export growth, suggesting that the decline in these countries this quarter is part of a long-term trend.

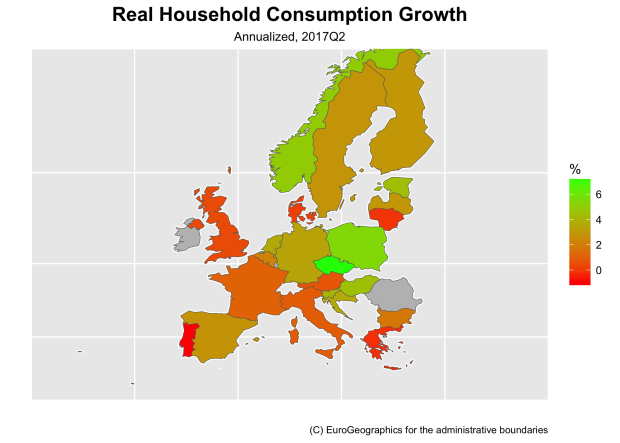

Household consumption maintained its annualized growth of 2% from 2017Q1 through the second quarter. Romania and Ireland, the two poles in this category, experienced a change in household spending on final goods and services of 11.3% and -4.5%, respectively. Save for Portuguese, Lithuanian, and Greek consumers, households from every other country in the EU increased their expenditures.

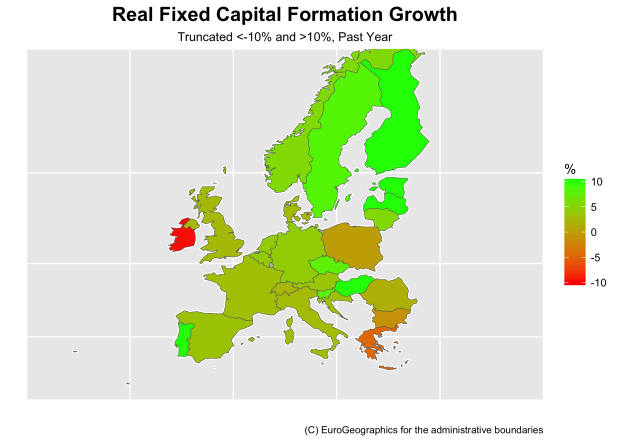

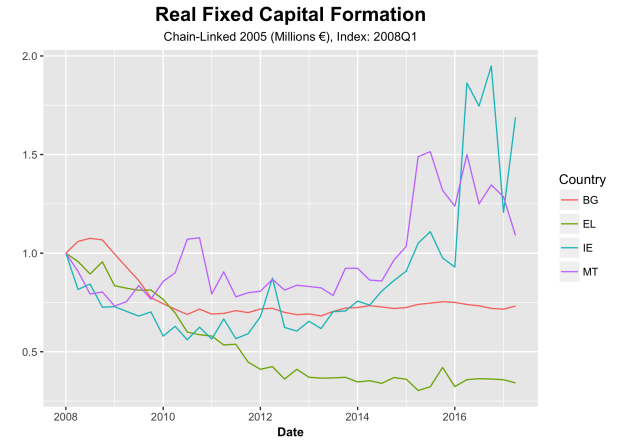

Moreover, capital formation in the EU increased by 2.5% since 2016Q2. The only member countries decreasing their investment in capital are Malta, Greece, Ireland, and Bulgaria.

Of these four countries, however, only Bulgaria and Greece remain below their pre-crisis levels in 2008.

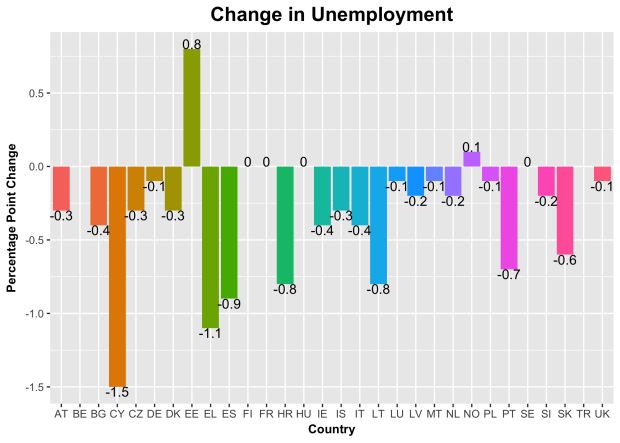

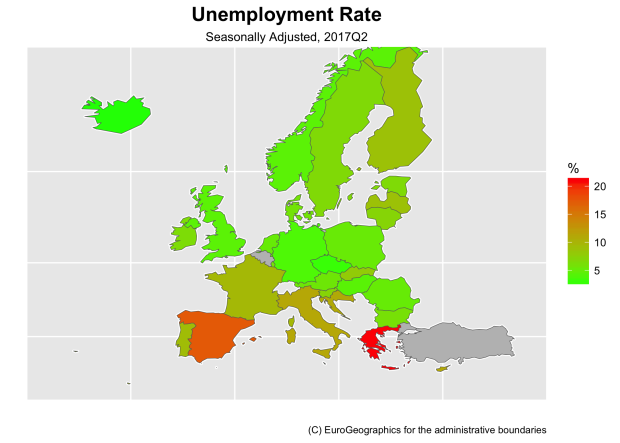

Additionally, the labor market has continued improving through 2017Q2. The Union as a whole decreased its unemployment rate from 8% to 7.7%, a downward trend reflected by almost every member economy.

Clearly, however, the Southern European economies are still lagging behind their Northern neighbors. Greece maintained its status as the weakest labor market with an unemployment rate remaining above 20%. The Spanish, Italian, and Croatian labor markets also remain particularly weak with over 10% of their labor force without work. The slow recovery of the French labor market also seems to have stalled. Not only does its unemployment rate remain more than double that of the United States, it also did not enjoy the same decline this quarter as its fellow EU members.

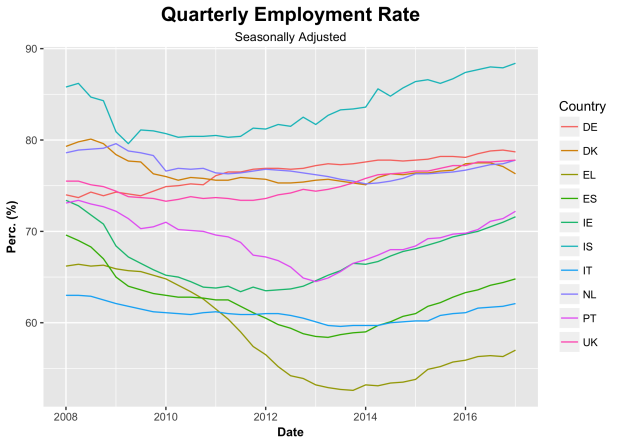

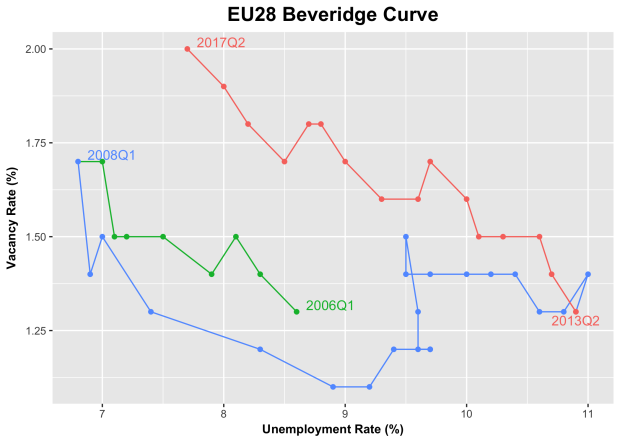

The employment to population ratio continued to improve for most member nations. The 2017Q2 numbers for many countries of interest have not yet been updated by Eurostat. Instead, we report the 2017Q1 numbers for this measure, which were not available to us back in June. The Beveridge curve for the Union seems to have almost completed its cycle this quarter. Since 2006Q1, however, the match efficiency between unemployed workers and vacancies seems to have decreased as indicated by the outward shift of the red portion of the curve relative to the green portion.

The Beveridge curve for the Union seems to have almost completed its cycle this quarter. Since 2006Q1, however, the match efficiency between unemployed workers and vacancies seems to have decreased as indicated by the outward shift of the red portion of the curve relative to the green portion.

These second quarter numbers give us confidence that things are in fact heading in the right direction for Europe. While there remain several areas of concern detailed here and elsewhere, the promising first quarter of 2017 does not seem to be a fluke.

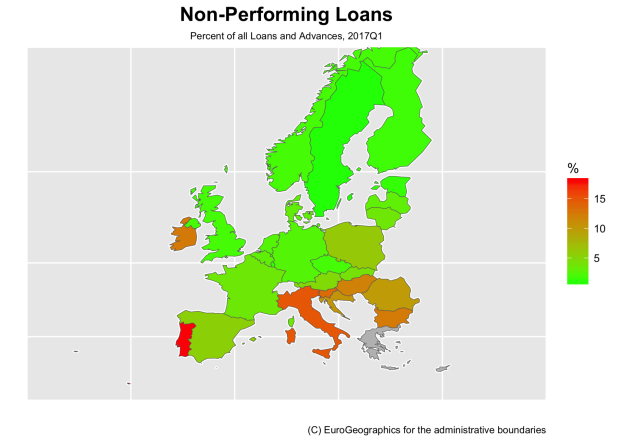

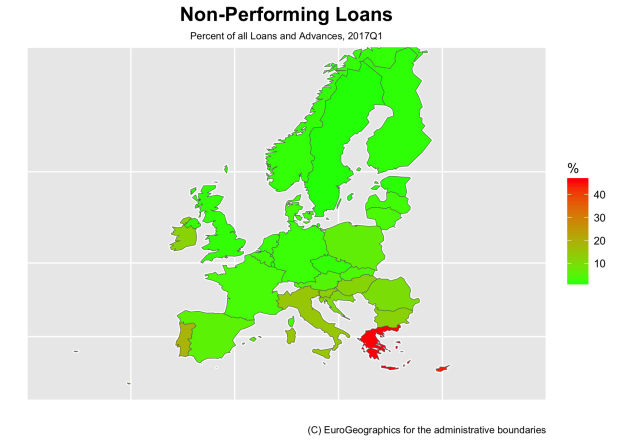

Given that Banco Popular’s problems can be linked in part to its massive portfolio of non-performing loans, this is a natural place to start for the rest of the Union. Indeed, it is evident that the Greek and Cypriot banking sectors are a great risk to their respective economies. During the first quarter of 2017, non-performing loans composed 46% and 43% of all loans in Greece and Cyprus, respectively, numbers above those of even Banco Popular prior to its crash. To get a better picture of the rest of Europe, we removed these two countries from our map.

Given that Banco Popular’s problems can be linked in part to its massive portfolio of non-performing loans, this is a natural place to start for the rest of the Union. Indeed, it is evident that the Greek and Cypriot banking sectors are a great risk to their respective economies. During the first quarter of 2017, non-performing loans composed 46% and 43% of all loans in Greece and Cyprus, respectively, numbers above those of even Banco Popular prior to its crash. To get a better picture of the rest of Europe, we removed these two countries from our map.